Lovely As Usual - Sustainable Lifestyle and Creation

In Conversation with Artist Xi, Min:Whispers of the Old, Echoes That Endure

In early spring 2026, visitors to WA Museum encounter an unexpected cast of characters. On the third floor, a sea turtle constructed from discarded plastic water bottles faces outward, its gaze aligned with the distant Great Wall. One floor below, a dragon pieced together from worn denim appears to blink as light shifts across its surface. Nearby, elephants emerge quietly from decommissioned hoodies, standing face to face with viewers.

These works are created by Xi, Min, an artist whose practice is rooted in reuse—not as statement, but as method. Rather than imposing form, she approaches materials as collaborators, attentive to what they suggest through wear, texture, and structure.

Lovely As Usual brings Xi, Min’s work into dialogue with the layered architecture and rural surroundings of WA Museum in Beigou Village. In the following conversation, she reflects on memory embedded in everyday objects, the quiet intelligence of materials, and how sustainability can exist not as a declaration, but as a way of continuing.

“Sustainability, to me, isn’t about moral instruction.

It’s about choosing to keep going, even when what you’re doing feels small.”

— Xi Min

Q1: Many of your works begin with everyday items—old jeans, cardboard, plastic bottles—things people usually discard. What gives these objects vitality in your eyes?

Xi, Min:

For me, vitality comes from time and emotional attachment. Even when an object is worn out, it carries traces of how it was used—how long it was worn, handled, or kept close. Those traces are a record of lived time.

From a material standpoint, wear is never neutral. Fading, fraying, distortion—these are all physical records of experience. A pair of jeans, once torn, stops being just clothing. It becomes a fragment of someone’s life.

When an object stops being defined by its original function and starts to act as a carrier of memory, it changes. A pair of jeans can become waves, scales, or the surface of an animal. That shift—from waste to narrative—is where its vitality reappears.

Zha-Yan Kite Made from Denim with Brocade Koi MotifQ2: You often describe your process as listening to materials. How do you “read” what a material wants to become?

Xi, Min:

I sometimes joke that my work is like helping materials find a second career. I’m not asking them to perform a role—I’m paying attention to their inherent qualities and placing them where those qualities make sense.

For example, denim zippers naturally curve. When I was making a horse, I struggled with the eyelids. I held a zipper against a light bulb, and suddenly the thickness and arc felt right. The metal ring even caught light like eyelashes. That solution later worked for snakes and cats as well.

Hoodies are similar. The raglan sleeves are wide and dense—they resemble an elephant’s trunk. The hood forms a symmetrical curve, like ears. Once those elements are recognized, the rest of the body follows with minimal alteration. The form emerges by respecting what’s already there.

Plastic bottles taught me something different. They resist flattening and tend to curl once cut. I originally planned to make a turtle with a flat shell, but that didn’t suit the material. Instead, I worked with large water jugs, rolling them into layered, cylindrical forms. That process led to a turtle that feels buoyant, almost suspended—more accurate to how the material behaves than how a turtle is usually depicted. At that point, I wasn’t designing; I was responding.

Q3: WA Museum is built with reclaimed tiles, stone, and wood, and is situated within a rural landscape near the Great Wall. How did you perceive the space, and how did your work interact with it?

Xi, Min:

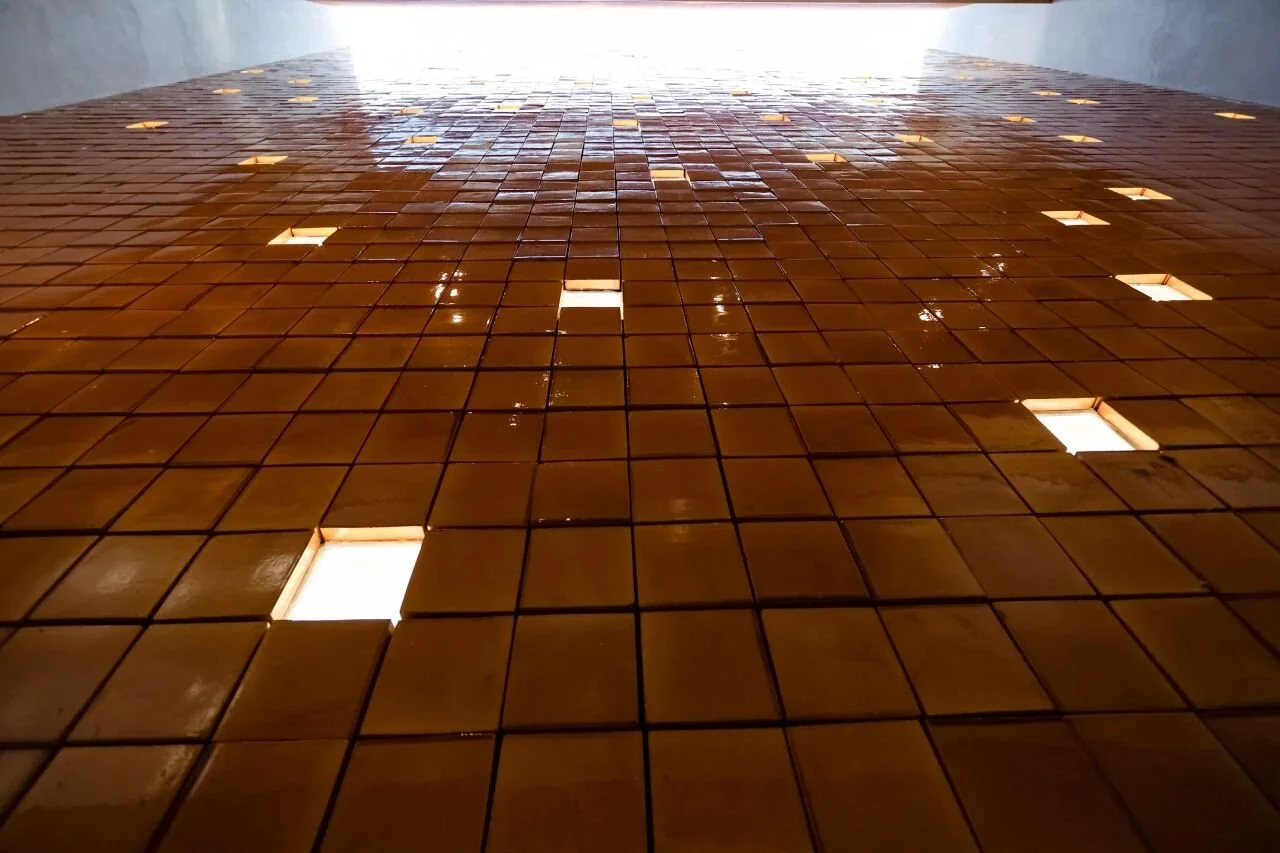

The museum feels grounded and contemporary at the same time. From the outside it appears solid and monumental, but inside the space is layered, with sloped ceilings and shifting perspectives. The use of reclaimed materials—tiles, bricks, stone—creates a sense of accumulated time.

That sensibility aligns closely with my work. The kite pieces I exhibited, composed of overlapping fish-scale forms, echo the layered surfaces of the museum’s tiled walls. Kites themselves carry cultural memory, so the connection felt natural.

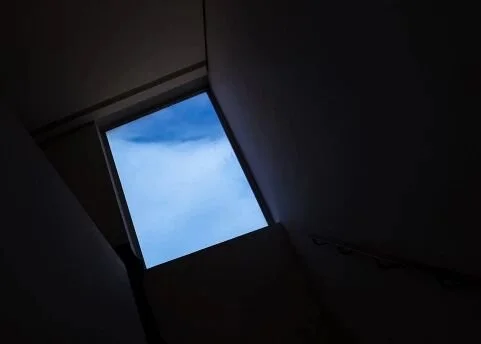

The most striking moment was on the third floor, where a window frames the Great Wall. Hanging the turtle there changed everything. It felt as though the work was no longer contained by the room, but placed into a larger landscape. The contrast between a small, fragile object and an expansive historical structure gave both a new presence.

Q4: How did the environment of Beigou Village influence you during this exhibition?

Xi, Min:

The pace of life here is very different from the city. In urban spaces, attention is constantly pulled elsewhere. In Beigou, I was able to slow down—sit in a courtyard, observe the mountains, and notice how the Great Wall cuts across the landscape.

Natural textures became especially visible. Fallen leaves reminded me of an earlier owl sculpture I made from leaf fragments. We even picked up plants with unexpected shapes that felt sculptural on their own.

The old kiln tiles were another revelation. Their colors—yellow, blue, green—once felt overwhelming to me. But here, under natural light, they appeared softened and grounded. Seeing how light interacts with material in this environment reshaped how I think about color and surface.

Q5: What do you hope visitors take away from Lovely As Usual?

Xi, Min:

I hope people feel a sense of surprise—that discarded things still have potential. I don’t expect to change how people behave. But many have told me that the work expresses something they already feel but struggle to articulate.

I’m not very verbal, so letting objects speak is enough for me. If the work resonates visually and emotionally, that connection can move in both directions—between viewer and object, and back to me.

For me, “lovely” is about vitality. The creatures I make aren’t broken or pitiful. They have character, like the cats that wander freely through the village. I hope sustainability can feel like that too—not heavy, but something that quietly accompanies daily life.

Q6: The Great Wall represents endurance and accumulation over time. How does that idea relate to your understanding of sustainable practice?

Xi, Min:

The Great Wall is immense—almost overwhelming. What I do is very small by comparison, like a single brick within it. All I can do is work with what I have, make what I believe in, and put it out into the world. If others see it and feel encouraged to do the same, then perhaps the Wall can continue a little further.

This is a process of continuation, a process shaped by time. The endurance of the Great Wall lies in the accumulation of individual bricks—each one fulfilling its role. My practice follows a similar logic. It is not a grand statement, but a quiet, manual act: stitching time together by hand, allowing old materials to carry memory, and giving discarded objects the chance to live again.

This kind of sustainability is not about moral instruction. It is a resilient choice—acknowledging one’s own smallness, and continuing anyway. The Great Wall does not require every brick to be extraordinary; it only requires each one to hold its place. Time does the rest. What I do is simply the work of one brick.

Curatorial Note

Xi Min’s work operates with a quiet insistence. Rather than critiquing consumption, she redirects attention to what remains. Rather than promoting sustainability as ideology, she presents it as practice.

At WA Museum, a turtle made from discarded plastic faces the Great Wall—one shaped by disposability, the other by endurance. Together, they suggest a different understanding of longevity: not resistance to time, but collaboration with it.

Lovely As Usual proposes that care, attention, and reuse are not grand gestures, but accumulative acts. What endures is not what is flawless or monumental, but what is allowed to continue—gently, persistently, and with intention.

Stay Connected with Xi Min on Xiaohongshu and Discover Her New Work| Venue Address |

No. 130, Beigou Village, Bohai Town, Huairou District, Beijing, China

| Business hour |

Monday to Sunday, 9:00-18:00

The public is warmly invited to visit Beigou Village and experience this living intersection of art and life at the foot of the Great Wall.